An example that isn't that artificial or intelligent

20 Jan 2017 By Jeff LeekEditor’s note: This is the second chapter of a book I’m working on called Demystifying Artificial Intelligence. The goal of the book is to demystify what modern AI is and does for a general audience. So something to smooth the transition between AI fiction and highly mathematical descriptions of deep learning. I’m developing the book over time - so if you buy the book on Leanpub know that there are only two chapters in there so far, but I’ll be adding more over the next few weeks and you get free updates. The cover of the book was inspired by this amazing tweet by Twitter user @notajf. Feedback is welcome and encouraged!

“I am so clever that sometimes I don’t understand a single word of what I am saying.” Oscar Wilde

As we have described it artificial intelligence applications consist of three things:

- A large collection of data examples

- An algorithm for learning a model from that training set.

- An interface with the world.

In the following chapters we will go into each of these components in much more detail, but lets start with a a couple of very simple examples to make sure that the components of an AI are clear. We will start with a completely artificial example and then move to more complicated examples.

Building an album

Lets start with a very simple hypothetical example that can be understood even if you don’t have a technical background. We can also use this example to define some of the terms we will be discussing later in the book.

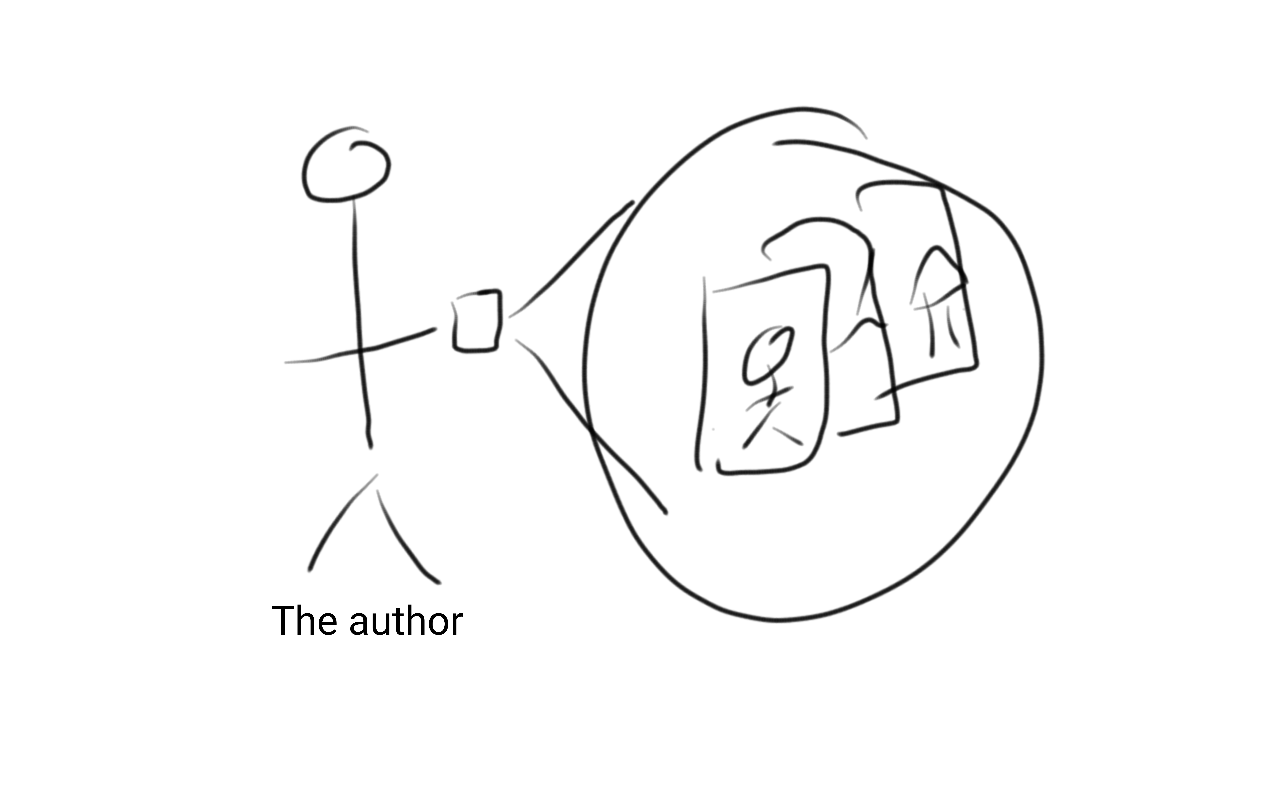

In our simple example the goal is to make an album of photos for a friend. For example, suppose I want to take the photos in my photobook and find all the ones that include pictures of myself and my son Dex for his grandmother.

If you are anything like the author of this book, then you probably have a very large number of pictures of your family on your phone. So the first step in making the photo alubm would be to stort through all of my pictures and pick out the ones that should be part of the album.

This is a typical example of the type of thing we might want to train a computer to do in an artificial intelligence application. Each of the components of an AI application is there:

- The data: all of the pictures on the author’s phone (a big training set!)

- The algorithm: finding pictures of me and my son Dex

- The interface: the album to give to Dex’s grandmother.

One way to solve this problem is for me to sort through the pictures one by one and decide whether they should be in the album or not, then assemble them together, and then put them into the album. If I did it like this then I myself would be the AI! That wouldn’t be very artificial though…imagine we instead wanted to teach a computer to make this album..

But what does it mean to “teach” a computer to do something?

The terms “machine learning” and “artificial intelligence” invoke the idea of teaching computers in the same way that we teach children. This was a deliberate choice to make the analogy - both because in some ways it is appropriate and because it is useful for explaining complicated concepts to people with limited backgrounds. To teach a child to find pictures of the author and his son, you would show her lots of examples of that type of picture and maybe some examples of the author with other kids who were not his son. You’d repeat to the child that the pictures of the author and his son were the kinds you wanted and the others weren’t. Eventually she would retain that information and if you gave her a new picture she could tell you whether it was the right kind or not.

To teach a machine to perform the same kind of recognition you go through a similar process. You “show” the machine many pictures labeled as either the ones you want or not. You repeat this process until the machine “retains” the information and can correctly label a new photo. Getting the machine to “retain” this information is a matter of getting the machine to create a set of step by step instructions it can apply to go from the image to the label that you want.

The data

The images are what people in the fields of artificial intelligence and machine learning call “raw data” (Leek, n.d.). The categories of pictures (a picture of the author and his son or a picture of something else) are called the “labels” or “outcomes”. If the computer gets to see the labels when it is learning then it is called “supervised learning” (Wikipedia contributors 2016) and when the computer doesn’t get to see the labels it is called “unsupervised learning” (Wikipedia contributors 2017a).

Going back to our analogy with the child, supervised learning would be teaching the child to recognize pictures of the author and his son together. Unsupervised learning would be giving the child a pile of pictures and asking them to sort them into groups. They might sort them by color or subject or location - not necessarily into categories that you care about. But probably one of the categories they would make would be pictures of people - so she would have found some potentially useful information even if it wasn’t exactly what you wanted. One whole field of artificial intelligence is figuring out how to use the information learned in this “unsupervised” setting and using it for supervised tasks

- this is sometimes called “transfer learning” (Raina et al. 2007) by people in the field since you are transferring information from one task to another.

Returning to the task of “teaching” a computer to retain information about what kind of pictures you want we run into a problem - computers don’t know what pictures are! They also don’t know what audio clips, text files, videos, or any other kind of information is. At least not directly. They don’t have eyes, ears, and other senses along with a brain designed to decode the information from these senses.

So what can a computer understand? A good rule of thumb is that a computer works best with numbers. If you want a computer to sort pictures into an album for you, the first thing you need to do is to find a way to turn all of the information you want to “show” the computer into numbers. In the case of sorting pictures into albums - a supervised learning problem - we need to turn the labels and the images into numbers the computer can use.

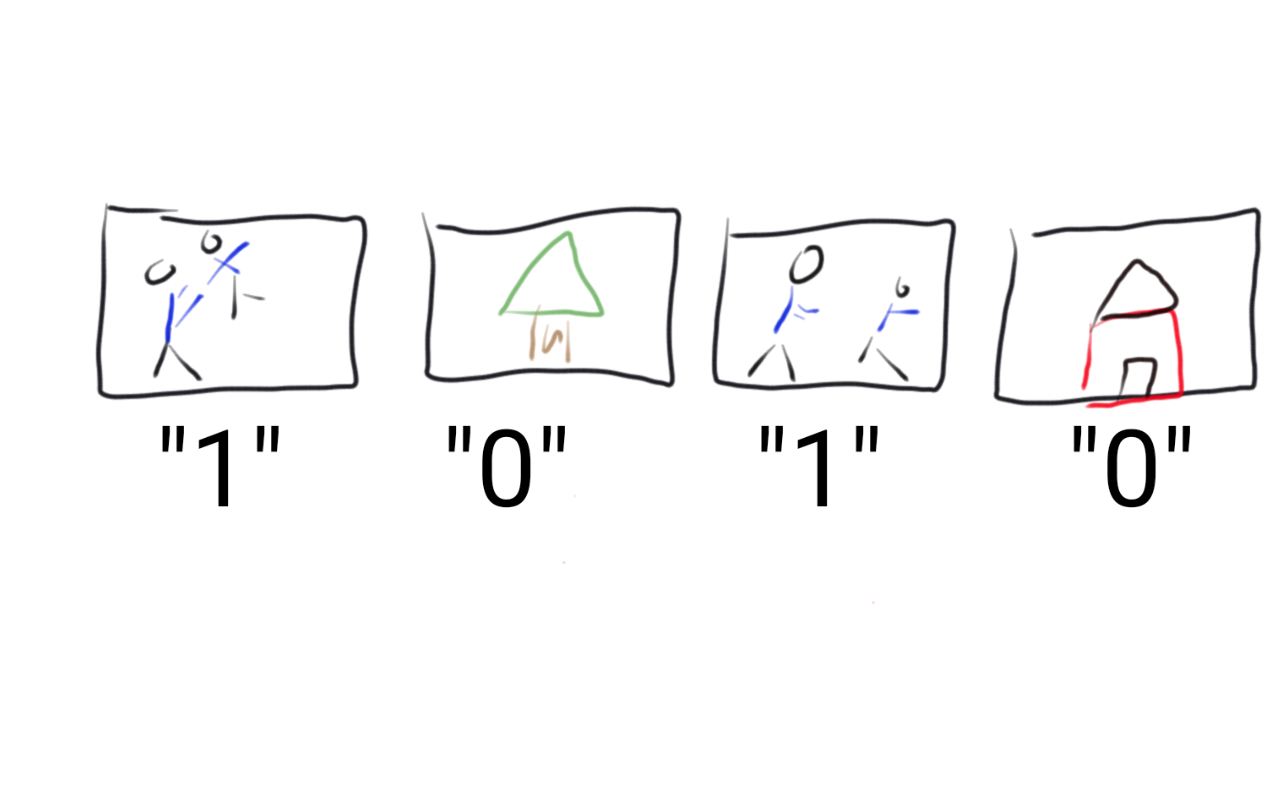

One way to do that would be for you to do it for the computer. You could take every picture on your phone and label it with a 1 if it was a picture of the author and his son and a 0 if not. Then you would have a set of 1’s and 0’s corresponding to all of the pictures. This takes some thing the computer can’t understand (the picture) and turns it into something the computer can understand (the label).

This process would turn the labels into something a computer could understand, it still isn’t something we could teach a computer to do. The computer can’t actually “look” at the image and doesn’t know who the author or his son are. So we need to figure out a way to turn the images into numbers for the computer to use to generate those labels directly.

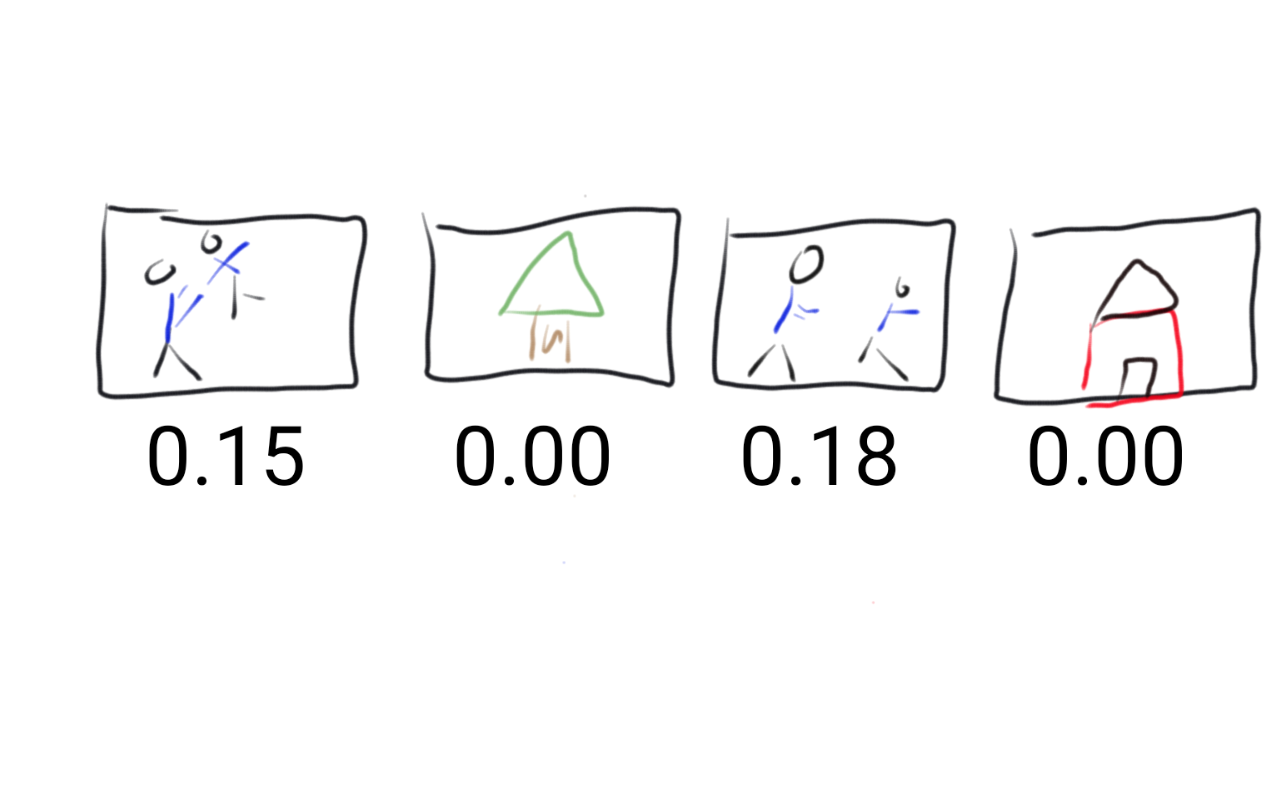

This is a little more complicated but you could still do it for the computer. Let’s suppose that the author and his son always wear matching blue shirts when they spend time together. Then you could go through and look at each image and decide what fraction of the image is blue. So each picture would get a number ranging from zero to one like 0.30 if the picture was 30% blue and 0.53 if it was 53% blue.

The fraction of the picture that is blue is called a “feature” and the process of creating that feature is called “feature engineering” (Wikipedia contributors 2017b). Until very recently feature engineering of text, audio, or video files was best performed by an expert human. In later chapters we will discuss how one of the most exciting parts about AI application is that it is now possible to have computers perform feature engineering for you.

The algorithm

Now that we have converted the images to numbers and the labels to numbers, we can talk about how to “teach” a computer to label the pictures. A good rule of thumb when thinking about algorithms is that a computer can’t “do” anything without being told very explicitly what to do. It needs a step by step set of instructions. The instructions should start with a calculation on the numbers for the image and should end with a prediction of what label to apply to that image. The image (converted to numbers) is the “input” and the label (also a number) is the “output”. You may have heard the phrase:

“Garbage in, garbage out”

What this phrase means is if the inputs (the images) are bad - say they are all very dark or hard to see. Then the output of the algorithm will also be bad - the predictions won’t be very good.

A machine learning “algorithm” can be thought of as a set of instructions with some of the parts left blank - sort of like mad-libs. One example of a really simple algorithm for sorting pictures into the album would be:

- Calculate the fraction of blue in the image.

- If the fraction of blue is above X label it 1

- If the fraction of blue is less than X label it 0

- Put all of the images labeled 1 in the album

The machine “learns” by using the examples to fill in the blanks in the instructions. In the case of our really simple algorithm we need to figure out what fraction of blue to use (X) for labeling the picture.

To figure out a guess for X we need to decide what we want the algorithm to do. If we set X to be too low then all of the images will be labeled with a 1 and put into the album. If we set X to be too high then all of the images will be labeled 0 and none will appear in the album. In between there is some grey area - do we care if we accidentally get some pictures of the ocean or the sky with our algorithm?

But the number of images in the album isn’t even the thing we really care about. What we might care about is making sure that the album is mostly pictures of the author and his son. In the field of AI they usually turn this statement around - we want to make sure the album has a very small fraction of pictures that are not of the author and his son. This fraction - the fraction that are incorrectly placed in the album is called the “loss”. You can think about it like a game where the computer loses a point every time it puts the wrong kind of picture into the album.

Using our loss (how many pictures we incorrectly placed in the album) we can now use the data we have created (the numbers for the labels and the images) to fill in the blanks in our mad-lib algorithm (picking the cutoff on the amount of blue). We have a large number of pictures where we know what fraction of each picture is blue and whether it is a picture of the author and his son or not. We can try each possible X and calculate the fraction of pictures in the album that are incorrectly placed into the album (the loss) and find the X that produces the smallest fraction.

Suppose that the value of X that gives the smallest faction of wrong pictures in the album is 30. Then our “learned” model would be:

- Calculate the fraction of blue in the image

- If the fraction of blue is above 0.1 label it 1

- If the fraction of blue is less than 0.1 label it 0

- Put all of the images labeled 1 in the album

The interface

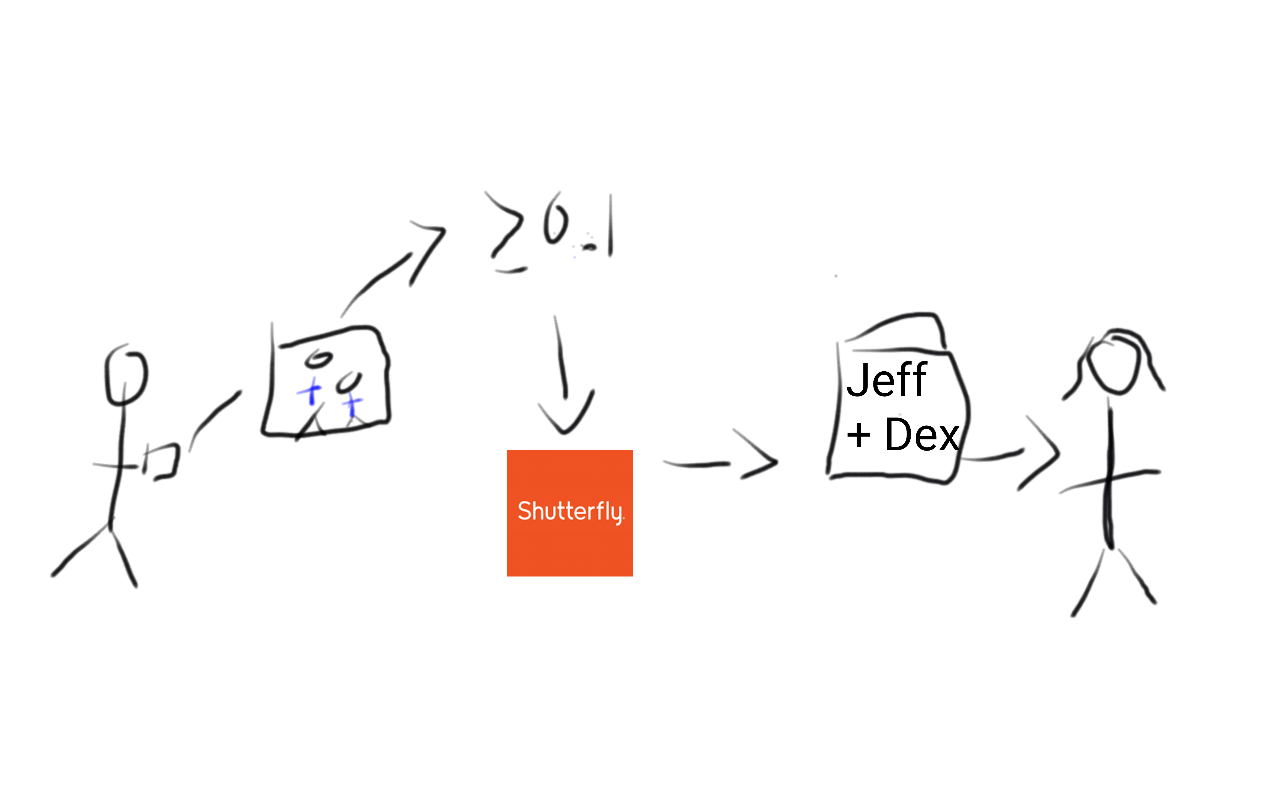

The last part of an AI application is the interface. In this case, the interface would be the way that we share the pictures with Dex’s grandmother. For example we could imagine uploading the pictures to Shutterfly and having the album delivered to Dex’s grandmother.

Putting this all together we could imagine an application using our trained AI. The author uploads his unlabeled photos. The photos are then passed to the computer program which calculates the fraction of the image that is blue, then applies a label according to the algorithm we learned, then takes all the images predicted to be of the author and his son and sends them off to be a Shutterfly album mailed to the authors’ mother.

If the algorithm was good, then from the perspective of the author the website would look “intelligent”. I just uploaded pictures and it created an album for me with the pictures that I wanted. But the steps in the process were very simple and understandable behind the scenes.

References

Leek, Jeffrey. n.d. “The Elements of Data Analytic Style.” {https://leanpub.com/datastyle}.

Raina, Rajat, Alexis Battle, Honglak Lee, Benjamin Packer, and Andrew Y Ng. 2007. “Self-Taught Learning: Transfer Learning from Unlabeled Data.” In Proceedings of the 24th International Conference on Machine Learning, 759–66. ICML ’07. New York, NY, USA: ACM.

Wikipedia contributors. 2016. “Supervised Learning.” https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Supervised_learning&oldid=752493505.

———. 2017a. “Unsupervised Learning.” https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Unsupervised_learning&oldid=760556815.

———. 2017b. “Feature Engineering.” https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Feature_engineering&oldid=760758719.

Follow us on twitter

Follow us on twitter