A Simple Explanation for the Replication Crisis in Science

24 Aug 2016 By Roger PengBy now, you’ve probably heard of the replication crisis in science. In summary, many conclusions from experiments done in a variety of fields have been found to not hold water when followed up in subsequent experiments. There are now any number of famous examples now, particularly from the fields of psychology and clinical medicine that show that the rate of replication of findings is less than the the expected rate.

The reasons proposed for this crisis are wide ranging, but typical center on the preference for “novel” findings in science and the pressure on investigators (especially new ones) to “publish or perish”. My favorite reason places the blame for the entire crisis on p-values.

I think to develop a better understanding of why there is a “crisis”, we need to step back and look across differend fields of study. There is one key question you should be asking yourself: Is the replication crisis evenly distributed across different scientific disciplines? My reading of the literature would suggest “no”, but the reasons attributed to the replication crisis are common to all scientists in every field (i.e. novel findings, publishing, etc.). So why would there be any heterogeneity?

An Aside on Replication and Reproducibility

As Lorena Barba recently pointed out, there can be tremendous confusion over the use of the words replication and reproducibility, so it’s best that we sort that out now. Here’s how I use both words:

-

replication: This is the act of repeating an entire study, independently of the original investigator without the use of original data (but generally using the same methods).

-

reproducibility: A study is reproducible if you can take the original data and the computer code used to analyze the data and reproduce all of the numerical findings from the study. This may initially sound like a trivial task but experience has shown that it’s not always easy to achieve this seemly minimal standard.

For more precise definitions of what I mean by these terms, you can take a look at my recent paper with Jeff Leek and Prasad Patil.

One key distinction between replication and reproducibility is that with replication, there is no need to trust any of the original findings. In fact, you may be attempting to replicate a study because you do not trust the findings of the original study. A recent example includes the creation of stem cells from ordinary cells, a finding that was so extraodinary that it led several laboratories to quickly try to replicate the study. Ultimately, seven separate laboratories could not replicate the finding and the original study was ultimately retracted.

Astronomy and Epidemiology

What do the fields of astronomy and epidemiology have in common? You might think nothing. Those two departments are often not even on the same campus at most universities! However, they have at least one common element, which is that the things that they study are generally reluctant to be controlled by human beings. As a result, both astronomers and epidemiologist rely heavily on one tools: the observational study. Much has been written about observational studies of late, and I’ll spare you the literature search by saying that the bottom line is they can’t be trusted (particularly observational studies that have not been pre-registered!).

But that’s fine—we have a method for dealing with things we don’t trust: It’s called replication. Epidemiologists actually codified their understanding of when they believe a causal claim (see Hill’s Criteria), which is typically only after a claim has been replicated in numerous studies in a variety of settings. My understanding is that astronomers have a similar mentality as well—no single study will result in anyone believe something new about the universe. Rather, findings need to be replicated using different approaches, instruments, etc.

The key point here is that in both astronomy and epidemiology expectations are low with respect to individual studies. It’s difficult to have a replication crisis when nobody believes the findings in the first place. Investigators have a culture of distrusting individual one-off findings until they have been replicated numerous times. In my own area of research, the idea that ambient air pollution causes health problems was difficult to believe for decades, until we started seeing the same associations appear in numerous studies conducted all around the world. It’s hard to imagine any single study “proving” that connection, no matter how well it was conducted.

Theory and Experimentation in Science

I’ve already described the primary mode of investigation in astronomy and epidemiology, but there are of course other methods in other fields. One large category of methods includes the controlled experiment. Controlled experiments come in a variety of forms, whether they are laboratory experiments on cells or randomized clinical trials with humans, all of them involve intentional manipulation of some factor by the investigator in order to observe how such manipulation affects an outcome. In clinical medicine and the social sciences, controlled experiments are considered the “gold standard” of evidence. Meta-analyses and literature summaries generally weight publications with controlled experiments more highly than other approaches like observational studies.

The other aspect I want to look at here is whether a field has a strong basic theoretical foundation. The idea here is that some fields, like say physics, have a strong set of basic theories whose predictions have been consistently validated over time. Other fields, like medicine, lack even the most rudimentary theories that can be used to make basic predictions. Granted, the distinction between fields with or without “basic theory” is a bit arbitrary on my part, but I think it’s fair to say that different fields of study fall on a spectrum in terms of how much basic theory they can rely on.

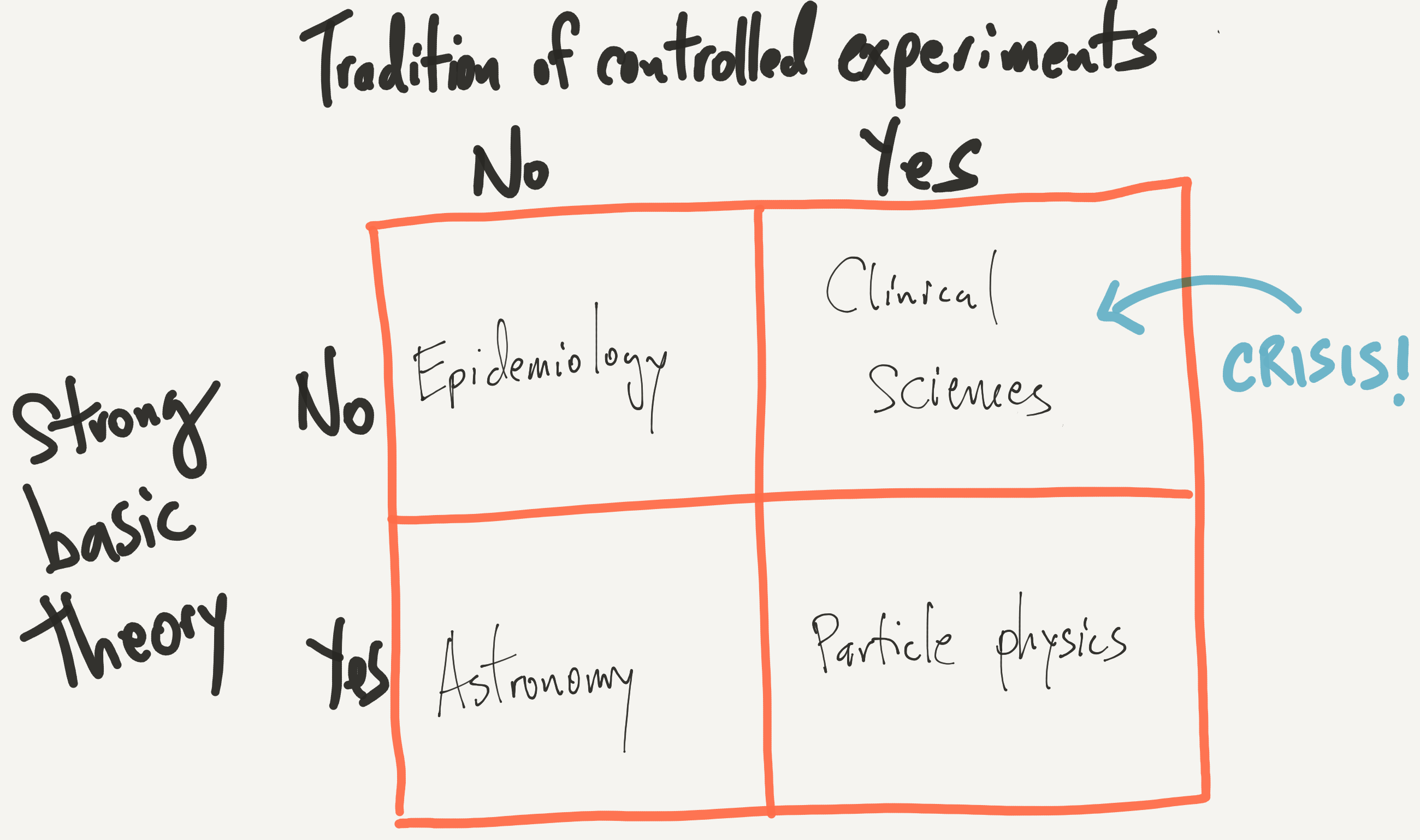

Given the theoretical nature of different fields and the primary mode of investigation, we can develop the following crude 2x2 table, in which I’ve inserted some representative fields of study.

My primary contention here is

The replication crisis in science is concentrated in areas where (1) there is a tradition of controlled experimentation and (2) there is relatively little basic theory underpinning the field.

Further, in general, I don’t believe that there’s anything wrong with the people tirelessly working in the upper right box. At least, I don’t think there’s anything more wrong with them compared to the good people working in the other three boxes.

In case anyone is wondering where the state of clinical science is relative to, say, particle physics with respect to basic theory, I only point you to the web site for the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. This is essentially a government agency with a budget of $124 million dedicated to advancing pseudoscience. This is the state of “basic theory” in clinical medicine.

The Bottom Line

The people working in the upper right box have an uphill battle for at least two reasons

- The lack of strong basic theory makes it more difficult to guide investigation, leading to wider ranging efforts that may be less likely to replicate.

- The tradition of controlled experimentation places high expectations that research produced here is “valid”. I mean, hey, they’re using the gold standard of evidence, right?

The confluence of these two factors leads to a much greater disappointment when findings from these fields do not replicate. This leads me to believe that the replication crisis in science is largely attributable to a mismatch in our expectations of how often findings should replicate and how difficult it is to actually discover true findings in certain fields. Further, the reliance of controlled experiements in certain fields has lulled us into believing that we can place tremendous weight on a small number of studies. Ultimately, when someone asks, “Why haven’t we cured cancer yet?” the answer is “Because it’s hard”.

The Silver Lining

It’s important to remember that, as my colleague Rafa Irizarry pointed out, findings from many of the fields in the upper right box, especially clinical medicine, can have tremendous positive impacts on our lives when they do work out. Rafa says

…I argue that the rate of discoveries is higher in biomedical research than in physics. But, to achieve this higher true positive rate, biomedical research has to tolerate a higher false positive rate.

It is certainly possible to reduce the rate of false positives—one way would be to do no experiments at all! But is that what we want? Would that most benefit us as a society?

The Takeaway

What to do? Here are a few thoughts:

- We need to stop thinking that any single study is definitive or confirmatory, no matter if it was a controlled experiment or not. Science is always a cumulative business, and the value of a given study should be understood in the context of what came before it.

- We have to recognize that some areas are more difficult to study and are less mature than other areas because of the lack of basic theory to guide us.

- We need to think about what the tradeoffs are for discovering many things that may not pan out relative to discovering only a few things. What are we willing to accept in a given field? This is a discussion that I’ve not seen much of.

- As Rafa pointed out in his article, we can definitely focus on things that make science better for everyone (better methods, rigorous designs, etc.).

Follow us on twitter

Follow us on twitter