A summary of the evidence that most published research is false

16 Dec 2013One of the hottest topics in science has two main conclusions:

- Most published research is false

- There is a reproducibility crisis in science

The first claim is often stated in a slightly different way: that most results of scientific experiments do not replicate. I recently got caught up in this debate and I frequently get asked about it.

So I thought I’d do a very brief review of the reported evidence for the two perceived crises. An important point is all of the scientists below have made the best effort they can to tackle a fairly complicated problem and this is early days in the study of science-wise false discovery rates. But the take home message is that there is currently no definitive evidence one way or another about whether most results are false.

- Paper: Why most published research findings are false. Main idea: People use hypothesis testing to determine if specific scientific discoveries are significant. This significance calculation is used as a screening mechanism in the scientific literature. Under assumptions about the way people perform these tests and report them it is possible to construct a universe where most published findings are false positive results. Important drawback: The paper contains no real data, it is purely based on conjecture and simulation.

- Paper: Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical research. Main idea: Many drugs fail when they move through the development process. Amgen scientists tried to replicate 53 high-profile basic research findings in cancer and could only replicate 6. Important drawback: This is not a scientific paper. The study design, replication attempts, selected studies, and the statistical methods to define “replicate” are not defined. No data is available or provided.

- Paper: An estimate of the science-wise false discovery rate and application to the top medical literature. Main idea: The paper collects P-values from published abstracts of papers in the medical literature and uses a statistical method to estimate the false discovery rate proposed in paper 1 above. Important drawback: The paper only collected data from major medical journals and the abstracts. P-values can be manipulated in many ways that could call into question the statistical results in the paper.

- Paper: Revised standards for statistical evidence. Main idea: The P-value cutoff of 0.05 is used by many journals to determine statistical significance. This paper proposes an alternative method for screening hypotheses based on Bayes factors. Important drawback: The paper is a theoretical and philosophical argument for simple hypothesis tests. The data analysis recalculates Bayes factors for reported t-statistics and plots the Bayes factor versus the t-test then makes an argument for why one is better than the other.

- Paper: Contradicted and initially stronger effects in highly cited research Main idea: This paper looks at studies that attempted to answer the same scientific question where the second study had a larger sample size or more robust (e.g. randomized trial) study design. Some effects reported in the second study do not match the results exactly from the first. Important drawback: The title does not match the results. 16% of studies were contradicted (meaning effect in a different direction). 16% reported smaller effect size, 44% were replicated and 24% were unchallenged. So 44% + 24% + 16% = 86% were not contradicted. Lack of replication is also not proof of error.

- Paper: Modeling the effects of subjective and objective decision making in scientific peer review. Main idea: This paper considers a theoretical model for how referees of scientific papers may behave socially. They use simulations to point out how an effect called “herding” (basically peer-mimicking) may lead to biases in the review process. Important drawback: The model makes major simplifying assumptions about human behavior and supports these conclusions entirely with simulation. No data is presented.

- Paper: Repeatability of published microarray gene expression analyses. Main idea: This paper attempts to collect the data used in published papers and to repeat one randomly selected analysis from the paper. For many of the papers the data was either not available or available in a format that made it difficult/impossible to repeat the analysis performed in the original paper. The types of software used were also not clear. Important drawback: This paper was written about 18 data sets in 2005-2006. This is both early in the era of reproducibility and not comprehensive in any way. This says nothing about the rate of false discoveries in the medical literature but does speak to the reproducibility of genomics experiments 10 years ago.

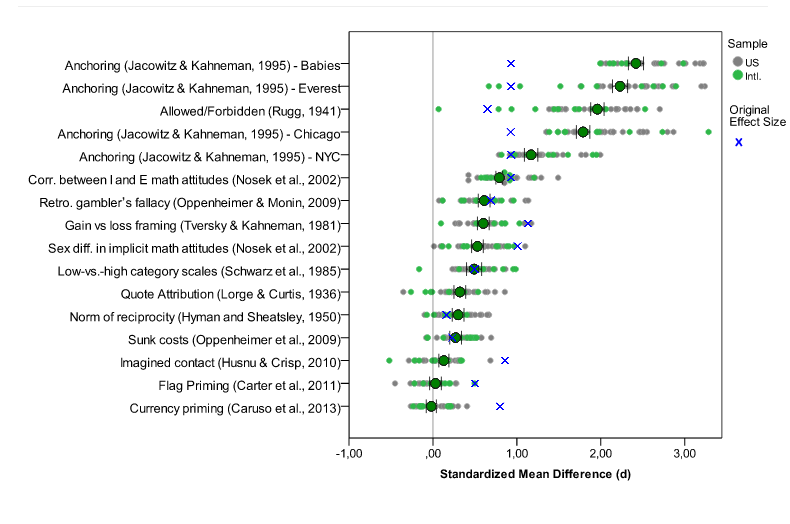

- Paper: Investigating variation in replicability: The “Many Labs” replication project. (not yet published) Main idea: The idea is to take a bunch of published high-profile results and try to get multiple labs to replicate the results. They successfully replicated 10 out of 13 results and the distribution of results you see is about what you’d expect (see embedded figure below). Important drawback: The paper isn’t published yet and it only covers 13 experiments. That being said, this is by far the strongest, most comprehensive, and most reproducible analysis of replication among all the papers surveyed here.

I do think that the reviewed papers are important contributions because they draw attention to real concerns about the modern scientific process. Namely

- We need more statistical literacy

- We need more computational literacy

- We need to require code be published

- We need mechanisms of peer review that deal with code

- We need a culture that doesn’t use reproducibility as a weapon

- We need increased transparency in review and evaluation of papers

Some of these have simple fixes (more statistics courses, publishing code) some are much, much harder (changing publication/review culture).

The Many Labs project (Paper 8) points out that statistical research is proceeding in a fairly reasonable fashion. Some effects are overestimated in individual studies, some are underestimated, and some are just about right. Regardless, no single study should stand alone as the last word about an important scientific issue. It obviously won’t be possible to replicate every study as intensely as those in the Many Labs project, but this is a reassuring piece of evidence that things aren’t as bad as some paper titles and headlines may make it seem.

Many labs data. Blue x's are original effect sizes. Other dots are effect sizes from replication experiments (http://rolfzwaan.blogspot.com/2013/11/what-can-we-learn-from-many-labs.html)

The Many Labs results suggest that the hype about the failures of science are, at the very least, premature. I think an equally important idea is that science has pretty much always worked with some number of false positive and irreplicable studies. This was beautifully described by Jared Horvath in this blog post from the Economist. I think the take home message is that regardless of the rate of false discoveries, the scientific process has led to amazing and life-altering discoveries.

Follow us on twitter

Follow us on twitter