02 Jan 2012

It’s the beginning of 2012 and statistics/data science has never been hotter. Some of the most important data is data collected about civic organizations. If you haven’t seen Bill Gate’s TED Talk about the importance of state budgets, you should watch it now. A major key to solving a lot of our economic problems lies in understanding and using data collected about cites and states.

U.S. cities and states are jumping on this idea and our own Baltimore was one of the earliest adopters. I thought I’d make a list of all the cities that have made an effort to make civic data public. Here are a few I’ve found:

There are also open data sites for many states:

Civic organizations are realizing that opening their data through APIs or by hosting competitions can lead to greater transparency, good advertising, and new and useful applications. If I had one data-related wish for 2012, it would be that the critical mass of data/statistics knowledge being developed could be used with these data to help solve some of our most pressing problems.

Update: Oh Canada! In the comments Ani Ruhil points to some Canadian cities/provinces with open data pages.

28 Dec 2011

Up until about 20 years ago, postdocs were scarce in Statistics. In contrast, during the same time period, it was rare for a Biology PhD to go straight into a tenure track position.

Driven mostly by the availability of research funding for those working in applied areas, postdocs are becoming much more common in our field and I think this is great. It is great for PhD students to expand their horizons during two years in which they don’t have to worry about teaching, committee meetings, or grant writing. It is also great for those of us fortunate enough to work with well-trained, independent, energetic, bright, and motivated fresh PhDs. Many of our best graduates are electing to postpone their entry into tenure track jobs in favor of postdocs. Also students from other fields, computer science and engineering in particular, are taking postdocs with statisticians. I think these are both good trends. If they continue, the result will be that, as a field, we will become more well-rounded and productive.

This trend has been particularly beneficial for me. Most of the postdocs I have hired have come to me with a CV worthy of a tenure track job. They have been independent and worked more as collaborators than advisees. So why pass on more $ and prestige? A PhD in Statistics/Computer Science/Engineering can be on a very specific topic and students may not gain any collaborative experience whatsoever. A postdoc at Hopkins Biostat provides a new experience in a highly collaborative environment, with access to world leaders in the biomedical sciences, and where we focus on development of applied tools. The experience can also improve a student’s visibility and job prospects, while delaying the tenure clock until they have more publications under their belts.

An important thing you should be aware of is that in many departments you can negotiate the start of a tenure track position. So seriously consider taking 1-2 years of almost 100% research time before commencing the grind of a tenure track job.

I’m not the only one who thinks postdocs are a good thing for our field and for biostatistics students. The column below was written by Terry Speed in November 2003 and is reprinted with permission from the IMS Bulletin, http://bulletin.imstat.org

In Praise of Postdocs

I don’t know what proportion of IMS members have PhDs (or an equivalent) in probability or statistics, but I’d guess it’s fairly high. I don’t know what proportion of those that do have PhDs would also have formal post-doctoral research experience, but here I’d guess it’s rather low.

Why? One possible reason is that for much of the last 40 years, anyone completing a PhD in prob or stat and wanting a research career, could go straight into one. Prospective employers of people with PhDs in our field—be they universities, research institutes, national labs or companies—don’t require their novices to have completed a postdoc, and most graduating PhDs are only to happy to go straight into their first job.

This is in sharp contrast with the biological and physical sciences, where it is rare to appoint someone to a tenure-track faculty or research scientist position without their having completed one or more postdocs.

Thee number of people doing postdocs in probability or statistics has been growing over the last 15 years. This is in part due to the arrival on the scene of institutes such as the MSRI, IMA, IPAM, NISS, NCAR, and recently the MBI and SAMSI in the US, the Newton Institute in the UK, the Fields Institute in Canada, the Institut Henri Poincaré in France, and others elsewhere around the world. In such institutes short- term postdoc positions go with their current research programs, and there are usually a smaller number continuing for longer periods.

It is also the case that an increasing number of senior researchers are being awarded research funds to support postdocs in prob or stat, often in the newer, applied areas such as computational biology.

And finally, it is has long been the case that many countries (Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, and the US, to name a few) have national grants supporting postdoctoral research in their own or, even better, another country. I think all of this is great, and would like to see this trend continue and strengthen.

Why do I think postdocs are a good thing? And why do I think young probabilists and statisticians should do one, even when they can get a good job without having done so?

For most of us, doing a PhD means getting totally absorbed in some relatively narrow research area for 2–3 years, treating that as the most important part of science for that time, and trying to produce some of the best work in that area. This is fine, and we get a PhD for our efforts, but is it good training for a lifelong research career? While it is obviously good preparation for doing more of the same, I don’t think it is adequate for research in general. I regard the successful completion of a PhD as (at least) evidence that the person in question can do research, but it doesn’t follow that they can go on and successfully do research in new area, or in a different environment, or without close supervision.

Postdocs give you the chance to broaden, to learn new technical skills, to become acquainted with new areas, and to absorb the culture of a new institution, all at a time when your professional responsibilities are far fewer than they would have been had you taken that first “real” job. The postdoc period can be a wonderful time in your scientific life, one which sees you blossom, building on the confidence you gained by having completed your PhD, in what is still essentially a learning environment, but one where you can follow your own interests, explore new areas, and still make mistakes. At the worst, you have delayed your entry into the workforce two or three years, and you can still keep on working in your PhD area if you wish. The number of openings for researchers in prob or stat doesn’t fluctuate so much on this time scale, so you are unlikely to be worse off than the earnings foregone. At best, you will move into a completely new area of research, one much better suited to your personal interests and skills, perhaps also better suited to market demand, but either way, one chosen with your PhD experience behind you. This can greatly enhance your long-term career prospects and more than compensate for your delayed entry into the workforce.

Students: the time to think about this is now [November], not just as you are about to file your dissertation. And the choice is not necessarily one between immediate security and career development: you might be able to have both. You shouldn’t shy from applying for tenure-track jobs and postdocs at the same time, and if offered the job you want, requesting (say) two years’ leave of absence to do the postdoc you want. Employers who care about your career development are unlikely to react badly to such a request.

21 Dec 2011

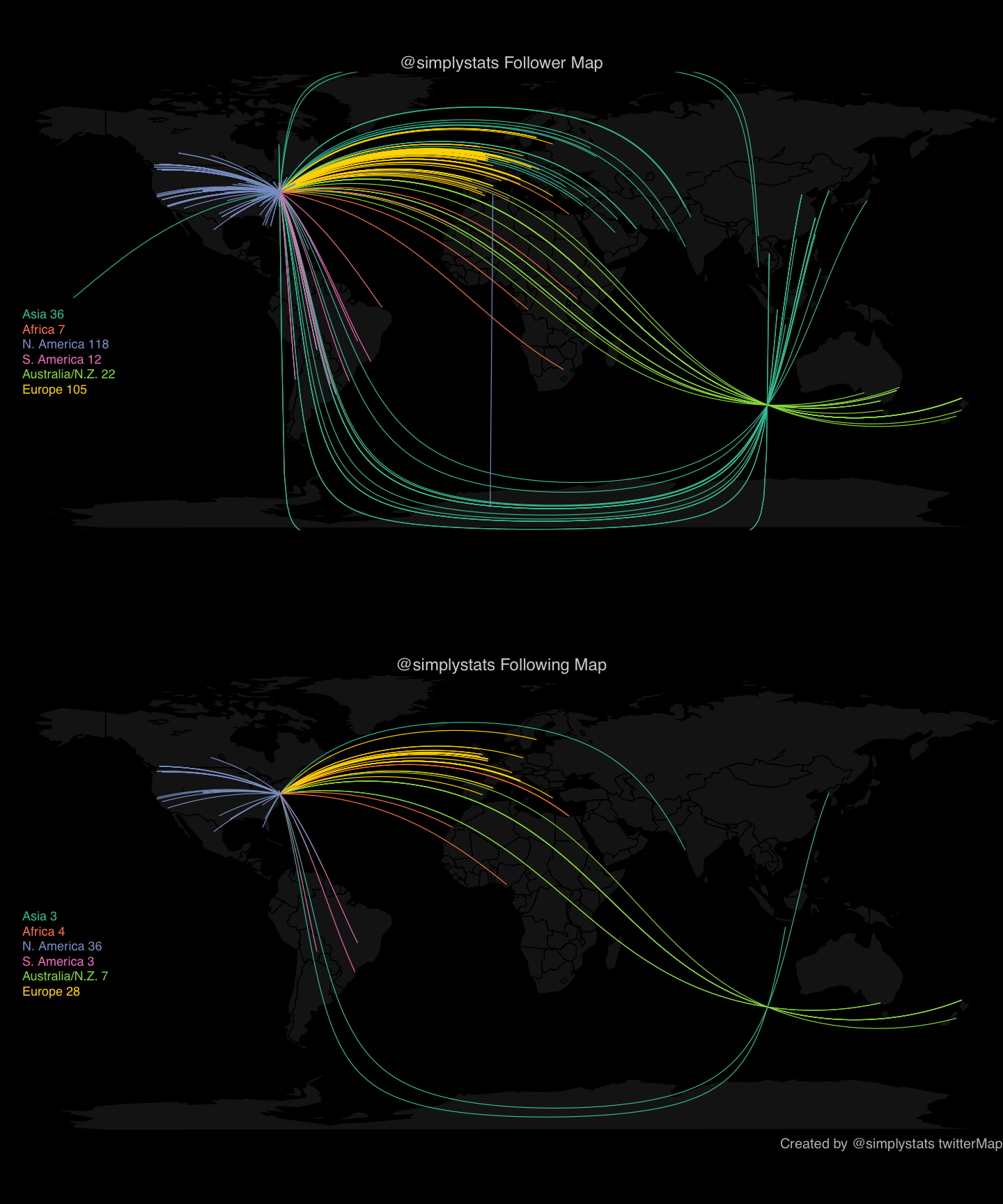

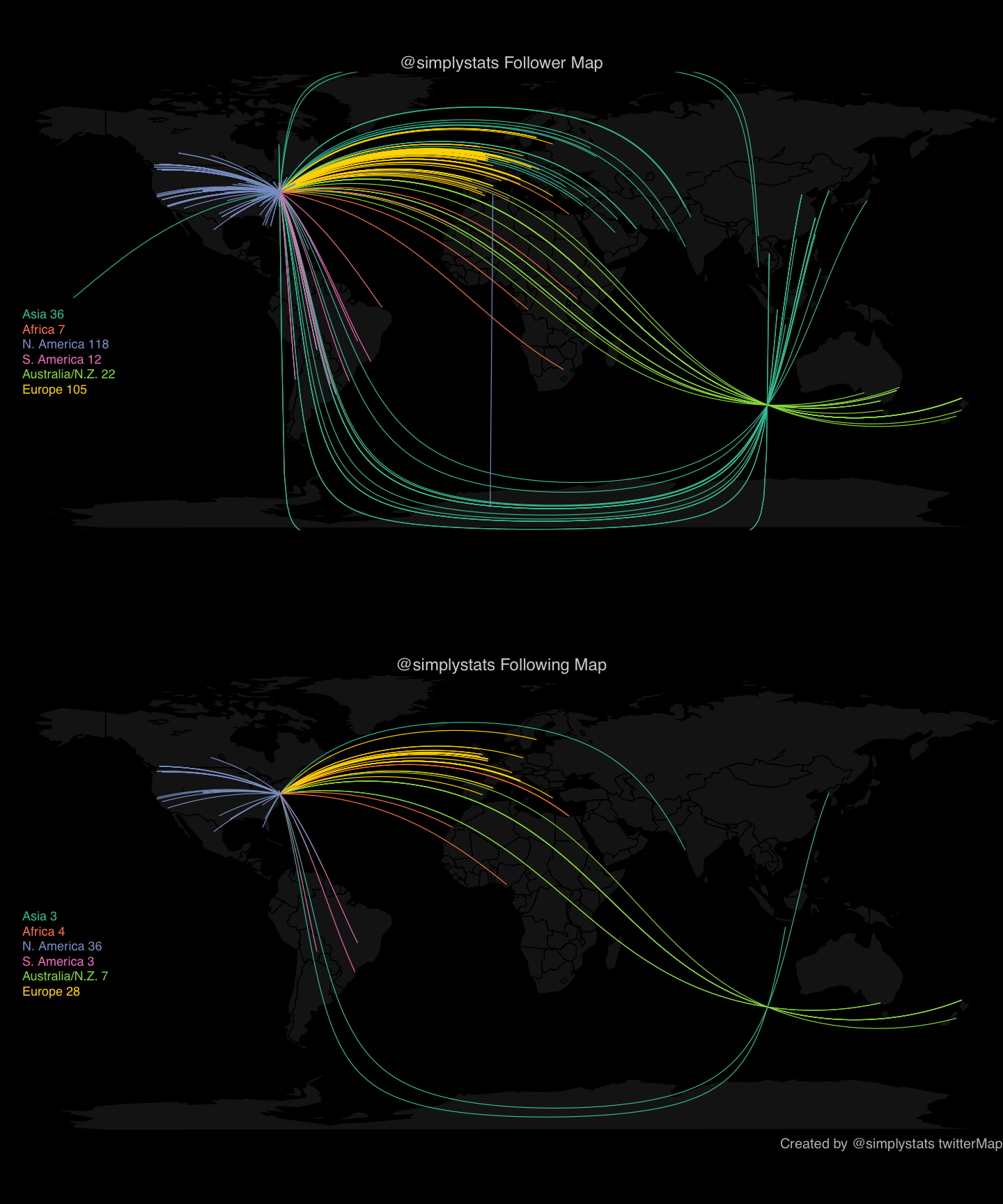

I wrote a little function to make a personalized map of who follows you or who you follow on Twitter. The idea for this function was inspired by some plots I discussed in a previous post. I also found a lot of really useful code over at flowing data here.

The function uses the packages twitteR, maps, geosphere, and RColorBrewer. If you don’t have the packages installed, when you source the twitterMap code, it will try to install them for you. The code also requires you to have a working internet connection.

One word of warning is that if you have a large number of followers or people you follow, you may be rate limited by Twitter and unable to make the plot.

To make your personalized twitter map, first source the function:

source(“http://biostat.jhsph.edu/~jleek/code/twitterMap.R”)

The function has the following form:

twitterMap <- function(userName,userLocation=NULL,fileName=”twitterMap.pdf”,nMax = 1000,plotType=c(“followers”,”both”,”following”))

with arguments:

- userName - the twitter username you want to plot

- userLocation - an optional argument giving the location of the user, necessary when the location information you have provided Twitter isn’t sufficient for us to find latitude/longitude data

- fileName - the file where you want the plot to appear

- nMax - The maximum number of followers/following to get from Twitter, this is implemented to avoid rate limiting for people with large numbers of followers.

- plotType - if “both” both followers/following are plotted, etc.

Then you can create a plot with both followers/following like so:

twitterMap(“simplystats”)

Here is what the resulting plot looks like for our Twitter Account:

If your location can’t be found or latitude longitude can’t be calculated, you may have to chose a bigger city near you. The list of cities used by twitterMap can be found like so:

library(maps)

data(world.cities)

grep(“Baltimore”, world.cities[,1])

If your city is in the database, this will return the row number of the world.cities data frame corresponding to your city.

Update: The bulk of the heavy lifting done by these functions is performed by Jeff Gentry’s very nice

twitteR package and

code put together by Nathan Yau over at FlowingData. This is really an example of standing on the shoulders of giants.

19 Dec 2011

As the academic job hunting season goes into effect many will be applying to a variety of different types of departments. In statistics, there is a pretty big separation between statistics departments, which tend to be in arts & sciences colleges, and biostatistics departments, which tend to be in medical or public health institutions. A key difference between these two types of departments is the funding model.

Statistics department faculty tend to be on 9- or 10-month salaries with funding primarily coming from teaching classes (research funding can be obtained for the summer months). Biostatistics departments faculty tend to have 12-month salaries with a large chunk of funding coming from research grants. Statistics departments are sometimes called “hard money” departments (i.e. tuition money is “hard”) while biostatistics departments are “soft money”. Grant money is considered “soft” because it has a tendency to go away a bit more easily. As long as students want to attend a university, there will always be tuition.

The biostatistics department at Johns Hopkins is a soft money department. We tend to get the bulk of our salaries from research project grants. Statisticians can play two roles on research grants: as a co-investigator/collaborator and as a principal investigator (PI). I guess that’s true of anyone, but statisticians are very commonly part of research projects as co-investigators because pretty much every research project these days will need statistical advice or methodological development. Researchers often have trouble getting their grants funded if they don’t have a statistician on board. So there’s often plenty of funding to go around for statisticians. But the real problem is getting enough time to do the research you want to do. If you’re spending all your time doing other people’s work, then sure you’re getting paid, but you’re not getting things done that will advance your career.

In a soft money department, I can think of two ways to go. The first is to write your own grants with you as the PI. That way you can guarantee funding for yourself to do the things you find interesting (assuming your grant is funded!). The other approach is to collaborate on a project where the work you need to do is work you would have done anyway. That can be a happy coincidence because then you don’t have to deal with the administrative burden of running a research project. But this approach relies a bit on luck and on the research environment at your institution.

Many job candidates tell me that they are worried about working in a soft money department because if they can’t get their grants funded then they will be in some sort of trouble. In hard money departments, at least the majority of their salary is guaranteed by the teaching they do. This is true to some extent, but I contend that they are worrying about the wrong thing, mainly money.

What job candidates should really be worried about is whether the department will support them in their career. Candidates should be looking for departments that mentor their junior faculty and create an environment in which it will be easy to succeed. If you’re in a department that routinely hangs their junior faculty out to dry, you can have all the hard money you want and you’ll still be unhappy. A soft money department that supports their junior faculty will make sure the right structure is in place for faculty to succeed.

Here are some things to look out for in any department, but perhaps more so in a soft money department:

- Is there administrative support staff to help with writing grants i.e. for drafting budgets, assembling biosketches, and other paperwork?

- Are their senior faculty around who have successfully written grants and would be willing to read your grants and give you feedback?

- Is the environment there sufficient for you to do the things you want to do? For example, are their excellent collaborators for you to work with? Powerful computing support? All these things will help you get an edge over people who don’t have easy access to these resources.

Besides having a good idea, the environment can play a key role in writing a good grant. For starters, if all your collaborators are in the same building as you, it makes it a lot easier to coordinate meetings to discuss ideas and to do the preparation. If you’re trying to work with 4 different people in 4 different institutions (maybe in different timezones), things just get a little harder and maybe you don’t get the feedback you need.

Similarly, if you have a strong computing infrastructure in place, then you can test it out beforehand and see what its capabilities are. If you need to purchase the same infrastructure for yourself as part of a grant, then you won’t know what it can do until you get and set it up. In our department, we are constantly buying new systems for our computing center and there are always glitches in the beginning with new equipment and new software. If you can avoid having to do this, it makes the grant a lot easier to write.

Lastly, I’ll just say that if you’re in the position of applying for tenure-track academic jobs, you’re probably not lazy. So you’re going to do your work no matter where you go. You just need to find a place where you can get things done.

Follow us on twitter

Follow us on twitter