Ultimate AI battle - Apple vs. Google

14 Jun 2016Yesterday, Apple launched its Worldwide Developer’s Conference (WWDC) and had its public keynote address. While many new things were announced, the one thing that caught my eye was the dramatic expansion of Apple’s use of artificial intelligence (AI) tools. I talked a bit about AI with Hilary Parker on the latest Not So Standard Deviations, particularly in the context of Amazon’s Echo/Alexa, and I think it’s definitely going to be an area of intense competition between the major tech companies.

Pretty much every major tech player is involved in AI—Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Microsoft—the list goes on. Recently, a some commentators have suggested that Apple in particular will never catch up with the likes of Google with respect to AI because of Apple’s strict stance on privacy and unwillingness to gather/aggregate data from all its users. However, yesterday at WWDC, Apple revealed a few clues about what it was up to in the AI world.

First, Apple mentioned deep learning more than a few times, including specifically calling out its use of LSTM in its Messages app and facial recognition in its Photos app. Previously, Apple had been rumored to be applying deep learning to its Siri assistant and its fingerprint sensor. At WWDC, Craig Federighi stressed Apple’s continued focus on privacy and how Apple does not need to develop “user profiles” server-side, but rather does most computation on-device (in this case, on the iPhone).

However, it can’t be that Apple does all its deep learning computation on the iPhone. These models tend to be enormous and take advantage of reams of data that can only be reasonablly processed server-side. Unfortunately, because most companies (Apple in particular) release few details about what they do, we may never how this works. But we can definitely speculate!

Apple vs. Google

I think the Apple/Google dichotomy provides an interesting opportunity to talk about how models can be learned using data in different ways. There are two approaches being represented here by Apple and Google:

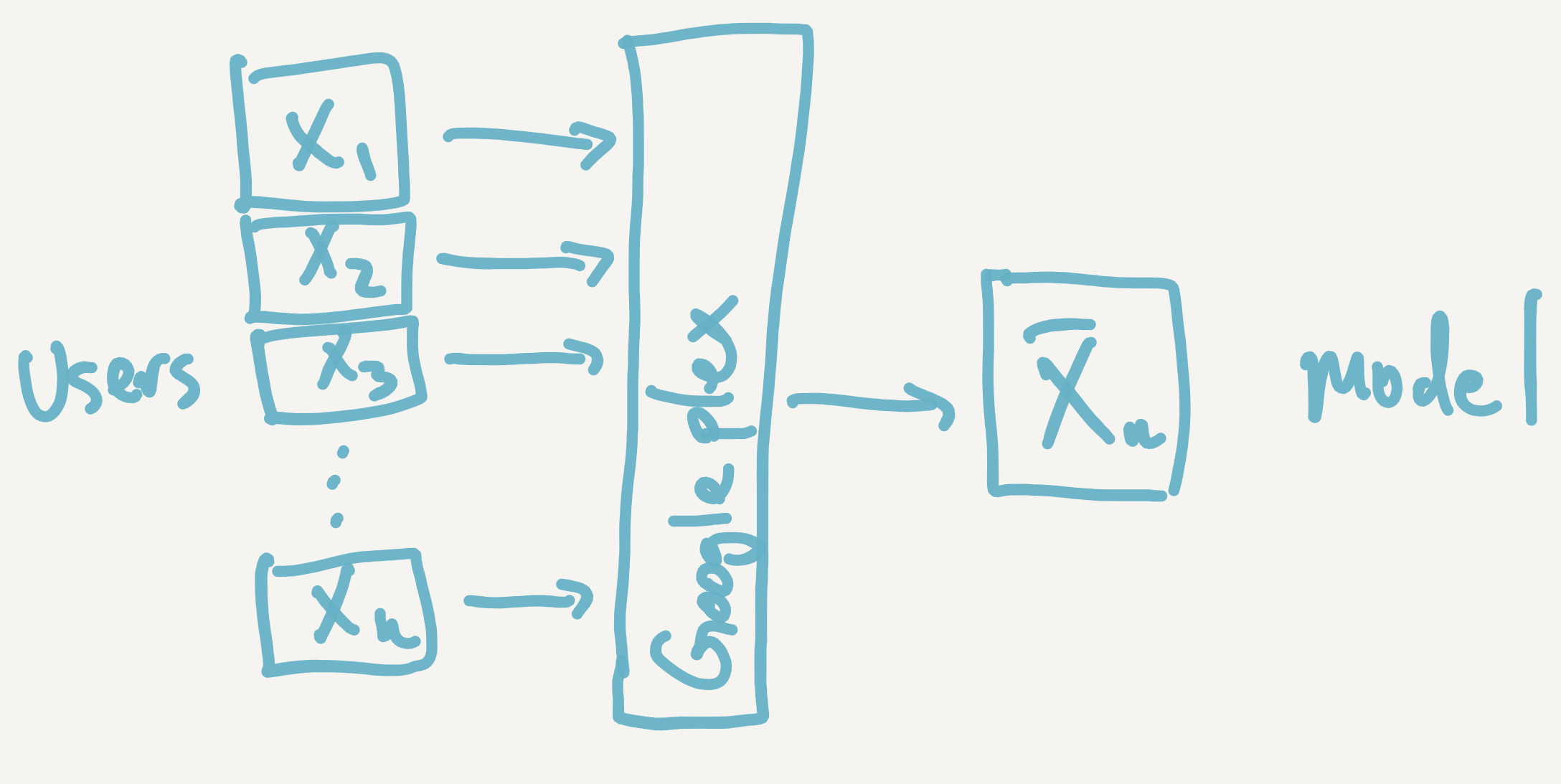

- Google way - Collect lots of data from users and store them on a server in the Googleplex somewhere. Then use that data to fit an enormous model that can predict when you’ve taken a picture of a cat. As users generate more data, bring that data back to the Googleplex and update/refine the model.

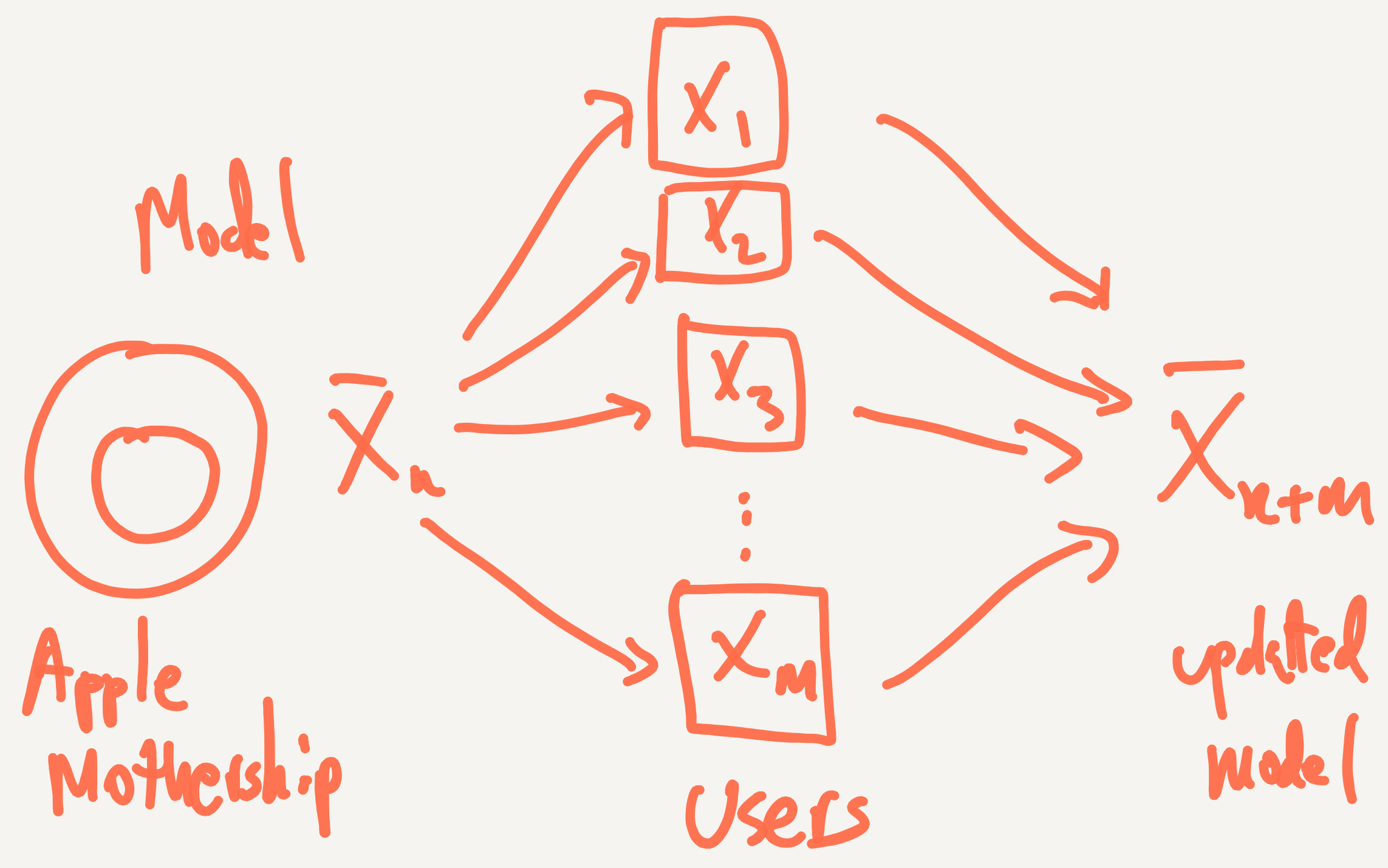

- Apple way - Build a “starter model” in the Apple Mothership. As users generate data on their phones, bring the model to the phone and update the model using just their data. Bring the updated model back to the Apple Mothership and leave the user’s data on the phone.

Perhaps the easiest way to understand this difference is with the arithmetic mean, which is perhaps the simplest “model”. Suppose you have a bunch of users out there and you want to compute the average of some attribute that they have on their phones (or whatever device). The first approach would be to get all that data and compute the mean in the usual way.

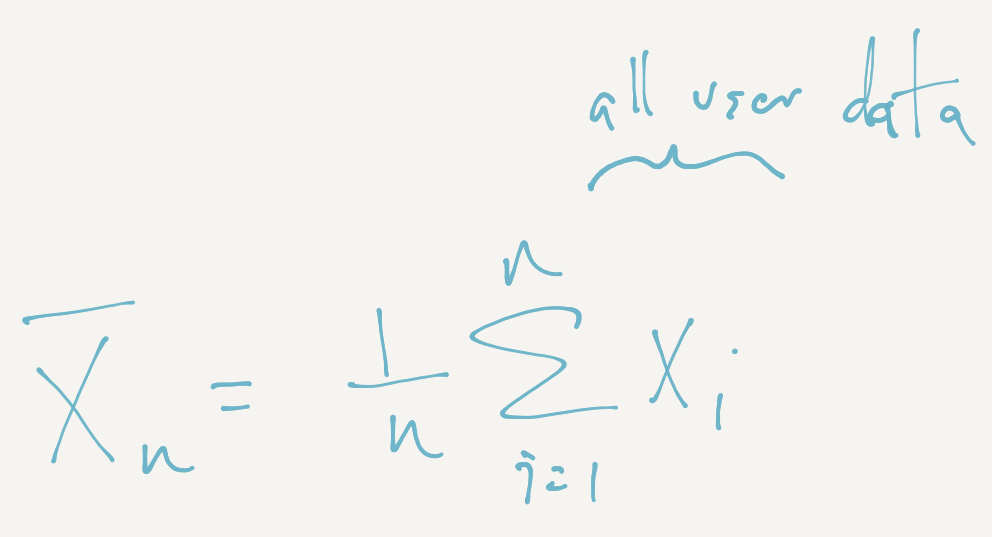

Once all the data is in the Googleplex, we can just use the formula

I’ll call this the “Google mean” because it requires that you get all the data X1 through Xn, then sum them up and divide by n. Here, each of the Xi’s represents the ith user’s data. The general principle here is to gather all the data and then estimate the model parameters server-side.

What if you didn’t want to gather everyone’s data centrally? Can you still compute the mean?

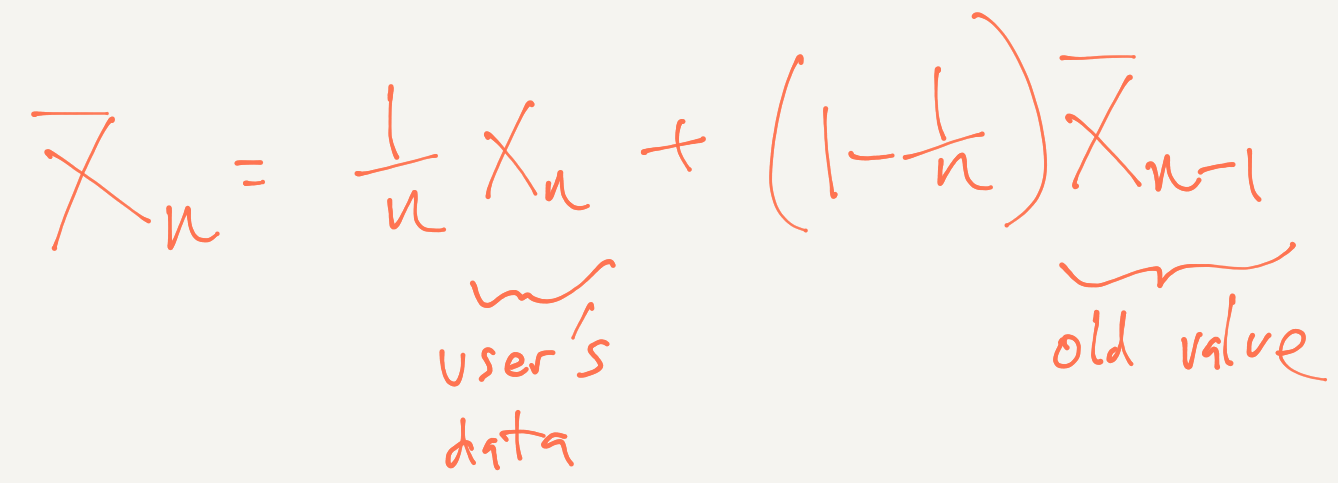

Yes, because there’s a nice recurrence formula for the mean:

We can call this the “Apple mean”. With this strategy, we can send our current estimate of the mean to each user, update our estimate by taking the weighted average of the old value and the new value, and then move on to the next user. Here, you send the model parameters out to the users, update those parameters and then bring the parameters back.

Which method is better? Well, in this case, both give you the same answer. In general, for linear models (like the mean), you can usually rework the formulas to build out either “whole data” (Google) approaches or “streaming” (Apple) approaches and get pretty much the same answer. But for non-linear models, it’s not so simple and you usually cannot achieve this kind of equivalence.

Clients and Servers

Balancing how much work is done on a server and how much is done on the client is an age-old computing problem and, over time, the balance of work between client and server seems to shift back and forth like a pendulum. When I was in grad school, we had so-called “dumb terminals” that were basically a screen that you used to login to the server. Today, I use my laptop for computing/work and that’s it. But I use the cloud for many other tasks.

The Apple approach definitely requires a “fatter” client because the work of integrating current model parameters with new user data has to happen on the phone. With the Google approach, all the phone has to do is be able to collect the data and send it over the network to Google.

The Apple approach is also closely related to what my colleagues Martin Lindquist and Brian Caffo refer to as “fusion science”, whereby Big Data and “Small Data” can be fused together via models to improve inference, but without ever having to actually combine the data. In a Bayesian context, you might think of the Big Data as making up the prior distribution and the Small Data as the likelihood. The Small Data can be used to update the model parameters and produce the posterior distribution, after which the Small Data can be thrown out.

And the Winner is…

It’s not clear to me which approach is better in terms of building a better model for prediction or inference. Sadly, we may never have enough details to find out, and will only be ablle to evaluate which approach is better by the performance of the systems in the marketplace. But perhaps that’s the way things should be evaluated in this case?

Follow us on twitter

Follow us on twitter